Healthcare organizations have worked hard to improve patient safety over the past several decades, however harm is still occurring at an unacceptable rate. Though the healthcare industry has made efforts (largely regulatory) to reduce patient harm, these measures are often not integrated with health system quality improvement efforts and may not result in fewer adverse events. This is largely because they fail to integrate regulatory data with improvement initiatives and, thus, to turn patient harm information into actionable insight.

Fully integrated clinical, cost, and operational data coupled with predictive analytics and machine learning are crucial to patient safety improvement. Tools that leverage this methodology will identify risk and suggest interventions across the continuum of care.

Avoiding patient harm is intrinsic to the work of healthcare professionals. Hippocrates (ca. 460–377 BCE), known as the Father of Modern Medicine, helped set this precedent when he said, “The physician must…have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.”

Contemporary medicine, however, still struggles to realize its primary mission. Today, researchers estimate that one in three hospitalized patients experiences preventable harm and over 400,000 individuals per year die from these injuries.

There is a gap in healthcare safety culture and the way health systems uses data (or think they use data) to understand patient harm and what to do about it. Much of the data collection is manual and not integrated with financial, operational, and other data, resulting in a fragmented approach to safety analytics that’s not actionable or predictive. Scores are recorded and boxes are checked, but the real work to make patients safer—closing the loop between information and action—is incomplete.

The status of patient safety moving forward, however, stands to improve. Despite the discouraging statistics above, in today’s era of data-driven healthcare, machine learning, and predictive analytics, the industry can turnaround decades of lost ground in patient safety and finally make much needed improvement in preventable errors. This white paper describes the problems in safety culture and how healthcare analytics and new-generation tools will fix them.

A Harvard Medical Practice Study defines patient harm as, “an injury that was caused by medical management (rather than the underlying disease) and that prolonged the hospitalization, produced a disability at the time of discharge, or both.” Adverse events can affect quality of life, delay treatment, lead to readmission, cause permanently disability, and more; at their worst, patients die.

Examples of patient harm include:

In his keynote address at the 2017 National Patient Safety Foundation Patient Safety Congress, Don Berwick, MD, president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, called out the “illusion of completeness” among the seven key areas of concern in patient safety. “There’s an illusion that we’ve worked on safety,” he stated.

Dr. Berwick explained that an industry emphasis on scores for patient harm events (e.g., central-line associated bloodstream infections [CLABSIs] and catheter-associated urinary tract infections [CAUTIs)] and compliance (e.g., medication reconciliation) has encouraged a “box-checking” attitude toward safety. Health systems may fail to develop real insight into risks for patient harm, and to develop appropriate intervention protocols.

“The concept of safety as a box-checking enterprise, where we start and finish, is lethal to patients of the future,” Dr. Berwick said.

With the transition from fee-for-service (FFS) to value-based reimbursement, patient safety extends beyond patient welfare to increasingly impact a health system’s financial bottom line. Reimbursement will be tied to patient safety (and quality metrics, as determined by CMS). Health systems that aren’t currently engaged in driving down patient harm, or have high readmission rates, risk reduced reimbursement.

This is a significant shift in how hospitals are compensated for services; formerly, added services due to complications or readmissions made the organization money. As the industry moves toward safety-driven reimbursement, however, health systems risk not only loss of revenue if they don’t prioritize safety, but also the possibility that insurance companies will refuse to work with them.

Two significant studies published in the 1990s put patient safety in the spotlight: Incidence of Adverse Events and Negligence in Hospitalized Patients — Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study (1991) and To Err Is Human (1999). The reports concluded, respectively, that a) patient harm occurs frequent and is often caused by substandard care and b) adverse events are more likely the result of systemic flaw, rather than individual negligence.

Further, adverse events and preventable errors in healthcare are the third leading cause of death in the U.S.—proving that while the industry may have done work and performed research to improve patient safety, it’s made little to no progress. In fact, patients today are experiencing 10 times the rate of preventable harm as they were in the 1990s.

If anything, the industry has regressed in the realm of patient safety. The system is inefficient: The industry repeatedly looks at the same HAIs when it needs to look at all-cause harm. Without a data-driven, all-cause approach to patient safety, history will continue to repeat itself.

Several issues stand out as weaknesses in the industry’s approach to patient safety:

Patient safety improvement centers on three actions: measure, intervene, and prevent. The health system must first identify and describe (measure) a safety issue, act to help the patient (intervene), and then avoid similar events in the future (prevent).

A proactive patient safety methodology includes four central aspects:

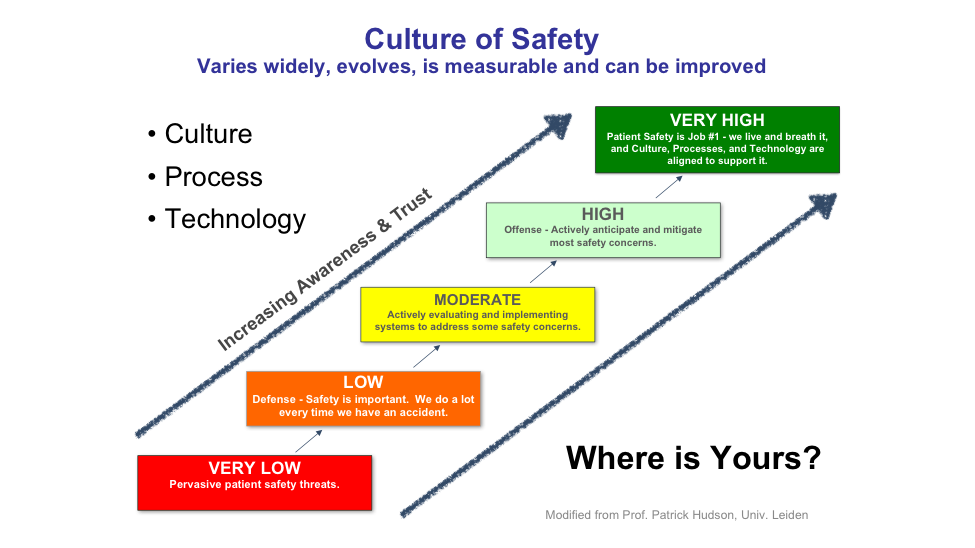

1. A sociotechnical approach: A sociotechnical approach combines culture, process, and technology (Figure 1). A laddered score can measure these elements to show how well a health system is doing in a culture of safety—from very low to very high.

2. All-cause harm: All-cause harm is a cultural value—one in which, instead of focusing solely on metrics, the organization embraces what it means to be a safe environment for patients and staff. This entails a just culture, where employees feel safe voluntarily reporting adverse events and preventable errors, and where a learning system around safety addresses factors in culture, process, and technology.

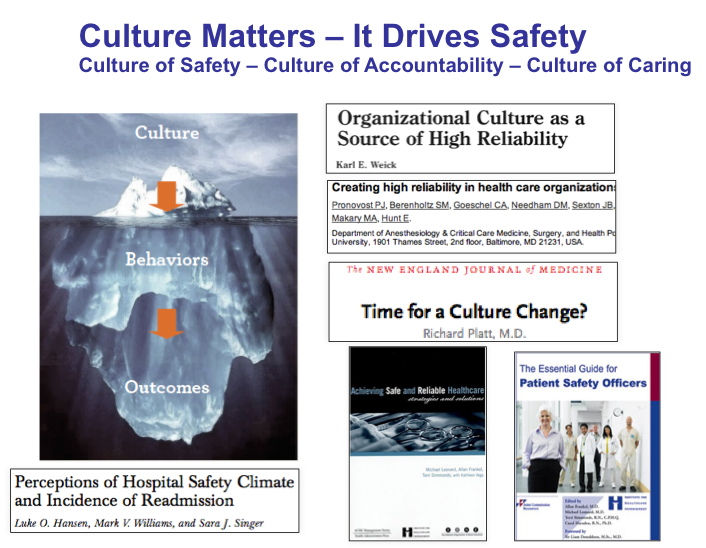

As To Err Is Human concluded, organizational culture is arguably the most influential dynamic in patient harm: “…errors are caused by faulty systems, processes, and conditions that lead people to make mistakes or fail to prevent them.” Several factors support the all-cause harm cultural value:

3. Transparency and patient engagement: Transparency—openly discussing risks for safety events with patients and families—ensures that everyone involved is aware of risk and can therefore put in place prevention and mitigation strategies. Engaging patients in conversations about prevention (e.g., falls, meds, pressure ulcers, etc.) makes them partners in their own safety. Effective engagement happens at the beginning of the healthcare experience (before admission), with education on how patients can help keep themselves safe and encouraging them to speak up if don’t feel they’re receiving safe care.

Patient engagement needs to outweigh compliance with guidelines and checklists. For example, when a pharmacist asks a patient if they want to be counseled about a prescription and the patient declines, the pharmacists checks the “no” box and moves on. Real engagement entails determining whether the patient thoroughly understands how to take their medication and risks associated with missing doses or dangerous interactions.

4. Breakdown of the shame-and-blame culture: Transparency extends to healthcare professionals, as communication and collaboration across all teams (e.g., surgical technicians, nurses, and physicians) is essential. A culture of shame and blame is too common in the industry—one in which, often for fear of repercussions or hierarchical professional structures, team members see an advantage in ascribing blame elsewhere, rather than addressing the adverse event or taking preventive measures.

Transparency among healthcare professionals relies on a cultural intervention—with buy-in at senior leadership and board levels to promote teamwork, collaboration, and communication, and avoid isolation and fragmentation between different factions of an organization (e.g., between leadership and frontline staff). A continued lack of full interoperability around safety will contribute to poor quality, high-cost care.

Fortunately, in the new era of data-driven patient safety, healthcare organizations will have incisive tools (Figure 3) to achieve better outcomes. Analytics tools will leverage integrated clinical, cost, and operational data and predictive analytics, machine learning, and more to address organizational weakness in patient safety and enable improvement.

Machine learning supports patient safety improvement with capabilities that are reactive, proactive, and fully integrated.

Data-driven patient safety initiatives are already at work in some health systems. The following success stories show how organizations are applying data, machine learning, and predictive analytics to reduced patient harm and improve care overall. The difference with the next-generation patient safety tools discussed in this paper is that they’ll address harm from an all-cause perspective, versus focusing on one specific adverse event at a time.

Data-Driven Process Improvement Raises Patient Safety for Highest-Risk Medication

Even though health systems widely use intravenous (IV) heparin (an anticoagulant) to prevent thrombosis, the medication carries a high risk for dosing errors. When an organization determined that its hospitals used several different IV heparin protocols (high variation), it saw a need for standard practices targeted at patients’ clinical needs. The health system developed an anticoagulation safety analytics application to monitor and better understand IV Heparin outcomes. As a result, the organization immediately improved the percentage of patients therapeutic by seven percent. It also made essential progress by reducing variation, and thereby risk of error, by establishing one systemwide guidelines and four systemwide protocols.

Leveraging Risk Assessment to Decrease LOS and Cost for PCI Patients

Percutaneous cardiac intervention (PCI) is a minimally-invasive alternative to open heart surgery for some patients, but it still carries risk. A health system that performs the highest volume of PCIs per year sought to lower the risk of bleeding—the most common non-cardiac complication associated with the procedure. The organization found bleeding events were increasing length of stay (LOS) and cost for patients undergoing PCI. To lower bleeding risk, the system leveraged its analytics platform to generate a bleeding risk assessment tool that allowed clinicians to focus interventions based on risk and to reduce complications. The organization has seen a 5.3 percentage point reduction in bleeding complication rate with PCI and $1.8M cost savings.

Reducing HAC Rates to Keep Kids Safe and Healthy

A nationally ranked pediatric center wanted to reduce its rates of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs)—such as central line-associated blood stream infections (CLASBIs) and pressure ulcers (PUs). It knew an intervention required major systematic changes. The organization needed access to data to support improvement efforts and build custom HAC applications. With an analytics platform that enabled automated, real-time reporting, it captured the needed information for improvement teams to develop HAC interventions. As a result, the health system reduced overall HAC cases by 30 percent (a $1.6 million savings), CLABSIs by 23 percent, PUs by 74 percent, and venous thromboembolisms (VTEs) by 68 percent.

Whether looking at the bottom line or, more significantly, the human face of patient harm and medical errors, safety is an issue that healthcare organizations must prioritize. People don’t come to hospitals to suffer from or die of preventable harm, yet it’s the third leading cause death in U.S. Furthermore, as value-based care escalates, patient harm will increasingly cost health systems money. No one gains when patients are hurt.

Patient safety won’t be achieved without quality improvement measures that include integrated clinical, cost, and operational data; automation; actionable insight; and full integration across the continuum of care. If organizations leverage predictive analytics and machine learning to make safety an overarching cultural goal, then other factors that define a successful health system will fall into place—including reimbursement and patient satisfaction scores. Everyone stands to gain with improved patient safety. As American physician and educator Arthur L. Bloomfield (1888–1962) explained, safety is an industry imperative: “There are some patients whom we cannot help; there are none whom we cannot harm.”

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Here are some articles we suggest:

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.