It might be a bit of a leap to associate quality data with improving the patient experience. But the pathway is apparent when you consider that physicians need data to track patient diagnoses, treatments, progress, and outcomes.

The data must be high quality (easily accessible, standardized, comprehensive) so it simplifies, rather than complicates, the physician’s job. This becomes even more important in the pursuit of population health, as care teams need to easily identify at-risk patients in need of preventive or follow-up care.

Patients engaged in their own care via portals and personal peripherals contribute to the volume and quality of data and feel empowered in the process. This physician and patient engagement leads to improved care and outcomes, and, ultimately, an improved patient experience.

Patient engagement—strategies that empower patients to be active in their own healthcare and motivate them to improve their personal health outcomes and reduce costs—is most effective when driven by the care team.

While physicians and care teams can’t force patients to engage in their own care, giving physicians the information and tools they need to engage patients is a foundational step in the process. It’s data that empowers physicians and care teams to engage their patients.

Given their own tools and access to information, patients will engage in their own care. This is important because engaged patients have greater trust in their providers and care, which ultimately leads to greater satisfaction and improved patient experiences. Engaged patients also tend to be healthier and have better outcomes.

Physician access to comprehensive, reliable data is one vital ingredient for efficiently engaging patients. The challenge, however, is the lack of a unified healthcare data source or true interconnectedness among multiple healthcare data sources. From individual EHRs, data warehouses, and the universe of data generated by personalized digital health devices, we are data rich, but collection and analysis poor.

I’m an internal medicine physician by training, and I’ve experienced the ups and downs of practicing medicine with varying amounts of data. On the one hand, I generally had solid information about encounters with each of my patients, though it wasn’t always as accessible as I would have liked. On the other hand, if a patient received care elsewhere, I’d have spotty data to work with. I had to take what I could get or invest time and effort into tracking down the information.

Today, however, as managing populations of patients becomes more and more essential to the viability of our healthcare system, spotty data will no longer suffice. Data aggregated from across the continuum of care is, in fact, key to enabling doctors and their care teams to manage populations of patients. Data drives efficiencies by letting care teams know which patients are high-risk or in need of preventive or follow-up care. With this data in hand, care teams are prepared to engage the patients who need it most—while gaining efficiency in the practice. The practice receives the data, an automated system flags the patient, the care team engages the right patients to come into the office, and the physician intervenes where that clinical expertise is required most.

Physicians typically want to engage patients, but they don’t have much time to do so. According to a RAND study from 2013, 80 percent of doctors said they were dissatisfied with EHRs because of increased documentation time and decreased patient engagement time. This is another reason why our clinical environments need to operate as efficiently as possible. When my clinic introduced patient portals to our workflow, I have to admit that, from my standpoint, it was sometimes a burden. It simply introduced more work. I would get to the end of a long day of seeing patients, only to find 20 messages from patients who required a response. Data-driven efficiencies would have given me more time to respond personally to messages that my care team had flagged as requiring my attention. That would have improved care, as well as patient and physician satisfaction.

Few things turn physicians off of data-driven approaches to managing patient populations more than bad data. In my practice, I’ve been handed lists of patients identified as lacking preventive care and, frankly, I knew the list wasn’t accurate. For example, I once received a list of patients to contact for a colonoscopy, and I knew that many of them had already been screened. I didn’t trust the list, so I didn’t want to work from it. My staff and I simply didn’t have the time to devote to schedule these patients for a colonoscopy if they didn’t really need one.

Unfortunately, bad data exists because it comes from multiple sources and is presented in multiple formats. Capture methods are inconsistent, resulting in both structured and unstructured data. It has subjective definitions depending on who is using it. And data is complex with multiple variables and changing regulatory requirements that call for changing data sets.

Quality data is essential. If care teams and physicians don’t have good data, they end up wasting effort and resources on patients who don’t need their attention. In the grand scheme of things, of course, every member of the population needs to be engaged to some extent. But practices seeking to increase quality and lower costs have limited resources, and it’s no secret that high-risk patients require our attention much, much more.

I’ve found from my experience both as a physician and in working for a company that specializes in data-driven quality improvement, that a culture of quality improvement goes a long way toward motivating physicians to engage their patients. All physicians want to deliver quality care to their patients. A data-driven environment keeps that quality on the physician’s mind at all times. A physician practicing in a quality culture does more than just see 25 to 30 patients a day and then go home. Data focuses care, drives evidence-based decision making, and enables process and workflow improvement. It allows physicians to concentrate on the things that matter most—improving lives, quality, and outcomes.

Achieving the triple aim of healthcare (i.e., improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care) depends on patients—with the guidance of their physicians—becoming more engaged in managing their health.

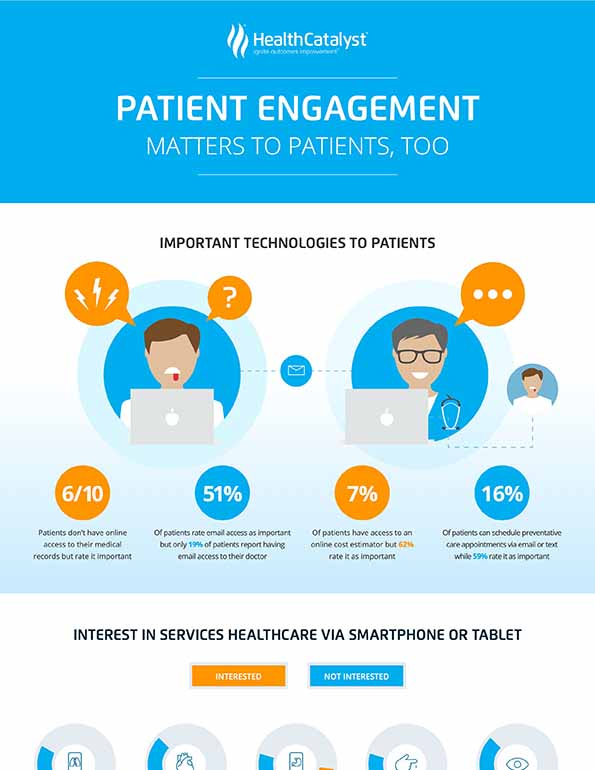

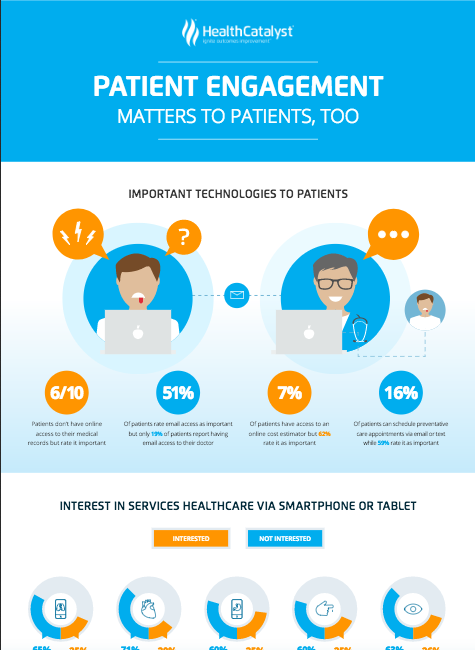

According to a Harris Poll conducted in 2015, 87 percent of patients said it’s either important or very important to have the ability to communicate with their doctor outside of an appointment, either by phone or email, to ensure a positive overall experience.

A separate Harris Poll conducted in 2014, showed that nearly half of Americans are extremely or very interested in being able to check their blood pressure (48 percent) or their heart and heartbeat for irregularities (47 percent) on their smartphone or tablet. Forty-three percent of Americans say they’re extremely or very interested in mobile apps and peripherals that can be used to track physical activity. These numbers are strong indicators that patients want to be engaged in their own healthcare, at least to some extent.

I’ll end with a personal note. Several years ago, my dad was diagnosed with cancer. My parents’ generation isn’t particularly tech-savvy, so they didn’t use patient portals or other methods of communication with the care team. Their engagement with their physician was limited to the specific amount of time they had with him during the appointment.

One of the joys of their lives was when my dad would have an appointment or procedure and then the doctor would call to share the results, ask how my dad was doing, and see if my parents had any questions. The brief amount of time that the doctor took to interact with my parents really was the highlight of their engagement. In fact, they would call me to let me know about it. They would tell me, “The doctor just called. Wasn’t that nice?”

I think about that and my own experiences reaching out to contact patients. That kind of interaction is what makes the practice of medicine truly satisfying. But the limiting factor is time. By using data to make doctors more efficient, we free up time for truly meaningful interactions.

Would you like to use or share these concepts? Download this presentation highlighting the key main points.

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/FNbIS8Grp5aRSx